by Simon Ayres

Another article in our series looking into human relationships with nature. The content of this article does not reflect the views of the charity which remains neutral on policy questions.

In a message to world leaders Nemonte Nenquimo, leader of the Waorani in the Amazon region, makes a plea for Western civilisation to learn from tribal people and to change its relationship with the planet. One of the striking aspects of the message is the indifference and contempt for the industrial-consumerist economy she refers to as Western civilisation.

Nemonte Nenquimo writes of the continuing plans to cut up our lands to stimulate an economy that has never benefited us. And states that as Indigenous peoples, we are fighting to protect what we love – our way of life, our rivers, the animals, our forests, life on Earth – and it’s time that you listened to us. It is significant that she talks of protecting their way of life, rather than seeking a stake in the market economy.

She goes on to denounce the extractive and polluting industrial activities that are destroying their land and much of the rest of the planet, drawing attention to the accompanying lies about environmental protection and benefits for local people – You forced your civilisation upon us and now look where we are…..

Nemonte Nenquimo states plainly, I have learned enough (and I speak shoulder to shoulder with my Indigenous brothers and sisters across the world) to know that you have lost your way.

A society that destroys the environment, poisons the water, pollutes the air, and creates dissatisfaction and artificial needs to drive consumerism is undoubtedly ‘lost’. This conclusion brings to mind the words of Salima Hirani * used in this context: “If you are lost, the best thing to do is retrace your steps to where you were before you got lost.” This article examines the proposition of retracing our steps, going back to living in balance with our ecosystems.

“We can’t go back” is often declared in the spirit of a thought-stopping slogan. What does ‘going back’ refer to here? In general, it is taken to mean returning to a simpler economic system practised by our ancestors. This could involve, for example: simpler technologies; providing for our real needs; not having artificial needs; practising localised economies; being more closely connected to production; living in harmony with our environment; not using money. In essence, the way of life that the Waorani people are fighting so hard to preserve.

I will present a selection of testaments of communities struggling to preserve a simpler way of life in the face of progress, of distress at losing it, and of people choosing to go back to a life more in balance with the rest of life on this planet. These examples indicate that it is possible to ‘go back’, and moreover that it is a desirable proposition from an individual or personal perspective. The desirability from a planetary perspective is unquestionable. First, I will briefly review the concept of ‘progress’ which provides the paradigm context for the notion that “we can’t go back”.

We like to tell ourselves a story about civilisation being on an inexorable path of social evolution towards a holy grail of technological omnipotence. But is it just a story, a myth? Considering that human societies have persisted for millions of years under stable economic and social conditions in balance with their environments, it can be argued that the current industrial-consumerist society is a temporary blip, and that we will return to the natural human state when we have woken up to the reality that this system we have created isn’t working. Perhaps the myth is hubris and delight at the tricks we can do. Perhaps the myth is a propaganda device to make us buy more stuff we don’t need.

The myth of progress was used as a propaganda device to justify colonialism. Professor Priya Satia, in her recently published book Time’s Monster – How History Makes History provides a critique of historians writing both during and after the British Empire. The violence, exploitation, racism, famine, pestilence and destruction – the products and tools of colonialism – were acknowledged to be bad, but justified as collateral in the magnificent march of progress of civilisation. We can’t avoid the impression that ‘progress’ was used as a distraction by powerful people to hide their real motives of increasing their own wealth and power. Perhaps the same dynamic is happening today in the context of commercialism.

In ironically circular or retroactive developments for the industrial economy, some of the most progressive ideas for tackling the pressing problems of our time are recognisably pre-industrial. A great example is the new idea to develop wind-powered cargo ships equipped with sails.

In a similar vein, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development published a Trade and Environment Review in 2013 titled Wake up before it is too late

The review found that small-scale regenerative farming systems are more productive than industrial-scale monoculture production, and additionally provide a number of public goods which industrial production impacts negatively. Traditional small-scale farming is presented as the solution to many global problems, such as climate change, poverty, pollution, soil loss, destruction of biodiversity, etc. It urges a rapid shift from industrial production towards small-scale mixed farming.

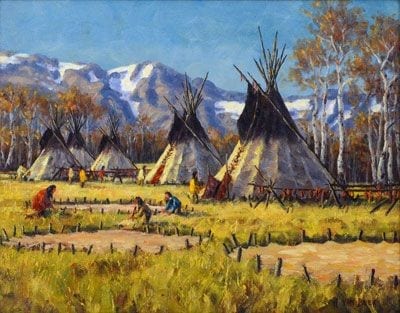

Here are a few testaments which throw into question the inevitability and desirability of civilisation and progress. Accounts from 18th and 19th Century North America describe the way of life of Native American tribal peoples and the attraction this had for many Europeans.

One example is the letter written around 1782 by Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur, titled Distresses of a Frontier Man .

As a farmer caught up in the American Revolution and vulnerable to raids by other Europeans on the American and British sides, Crèvecoeur considers the option of taking his family to live in safety with the local Native American tribe. His unfamiliarity with that lifestyle and his bias in favour of European culture cause him to hesitate about this prospect. Yet he knows enough about his tribal neighbours and the good experiences of other Europeans to give him optimism.

Crèvecoeur writes of a great village far removed from the accursed neighbourhood of Europeans, its inhabitants live with more ease, decency, and peace, than you imagine: where, though governed by no laws, yet find, in uncontaminated simple manners, all that laws can afford. Their system is sufficiently complete to answer all the primary wants of man, and to constitute him a social being, such as he ought to be in the great forest of nature.

Here, Crèvecoeur compares the different lifestyle impartially:

I have considered in all its future effects and tendencies, the new mode of living we must pursue, without salt, without spices, without linen and with little other clothing; the art of hunting, we must acquire, the new manners we must adopt, the new language we must speak; the dangers attending the education of my children we must endure. These changes may appear more terrific at a distance perhaps than when grown familiar by practice: what is it to us, whether we eat well made pastry, or pounded alagriches; well roasted beef, or smoked venison; cabbages, or squashes? Whether we wear neat home-spun or good beaver; whether we sleep on feather-beds, or on bear-skins? The difference is not worth attending to.

Crèvecoeur writes of thousands of Europeans who chose to remain with the Native Americans when given a chance to return to European society. And he had heard of not one single ‘Indian’ when given the chance to live as an equal in the colonists’ towns who didn’t prefer to return to their tribe.

By what power does it come to pass, that children who have been adopted when young among these people, can never be prevailed on to readopt European manners? Many an anxious parent I have seen last war, who at the return of the peace, went to the Indian villages where they knew their children had been carried in captivity; when to their inexpressible sorrow, they found them so perfectly Indianised, that many knew them no longer, and those whose more advanced ages permitted them to recollect their fathers and mothers, absolutely refused to follow them, and ran to their adopted parents for protection against the effusions of love their unhappy real parents lavished on them! Incredible as this may appear, I have heard it asserted in a thousand instances, among persons of credit. In the village of——, where I purpose to go, there lived, about fifteen years ago, an Englishman and a Swede, whose history would appear moving, had I time to relate it. They were grown to the age of men when they were taken; they happily escaped the great punishment of war captives, and were obliged to marry the Squaws who had saved their lives by adoption. By the force of habit, they became at last thoroughly naturalised to this wild course of life. While I was there, their friends sent them a considerable sum of money to ransom themselves with. The Indians, their old masters, gave them their choice, and without requiring any consideration, told them, that they had been long as free as themselves. They chose to remain; and the reasons they gave me would greatly surprise you: the most perfect freedom, the ease of living, the absence of those cares and corroding solicitudes which so often prevail with us; the peculiar goodness of the soil they cultivated, for they did not trust altogether to hunting; all these, and many more motives, which I have forgot, made them prefer that life, of which we entertain such dreadful opinions.

The story is recounted of a farming neighbour of Crèvecoeur who, some years ago, received from a good old Indian, who died in his house, a young lad, of nine years of age, his grandson. He kindly educated him with his children, and bestowed on him the same care and attention in respect to the memory of his venerable grandfather, who was a worthy man. He intended to give him a genteel trade, but in the spring season when all the family went to the woods to make their maple sugar, he suddenly disappeared; and it was not until seventeen months after, that his benefactor heard he had reached the village of Bald Eagle, where he still dwelt.

On mental health he writes, Without temples, without priests, without kings, and without laws, they are in many instances superior to us; and the proofs of what I advance, are, that they live without care, sleep without inquietude, take life as it comes, bearing all its asperities with unparalleled patience, and die without any kind of apprehension for what they have done, or for what they expect to meet with hereafter. What system of philosophy can give us so many necessary qualifications for happiness? They most certainly are much more closely connected with nature than we are…

As Crèvecoeur wonders so articulately, There must be something more congenial to our native dispositions, than the fictitious society in which we live; or else why should children, and even grown persons, become in a short time so invincibly attached to it?

A contemporary example of choosing to leave civilization to live a tribal lifestyle is Stephanie Fuchs, originally from Hamburg, who married into the Masai tribe of Tanzania . She is very positive about the Masai people and their way of life that she has adopted.

They are conservationists. They know how to live in tune with nature, so if you gave the world to them, the world would still be intact. We wouldn’t have all the issues that we have if everyone lived like the Masai, and everyone had this sort of traditional knowledge that they have to live in tune with nature. They respect nature, they cherish nature, and this by itself makes them better people…….

Their way of life is superior to ours – in tune with nature. They have land, they are rich, they have everything that you need to live….. They know how to live sustainably….. We don’t know what it means to live a life true to ourselves and a life true to our planet, a life true to nature.

In Britain, the enclosures and clearances represented a brutal removal of people from the land as it progressed at different times in different regions over many centuries. In time, the majority of the population lost their rights to economic access to the land. Many went to work in factories in the cities, the factories often owned by the landowners responsible for the clearances and who now conveniently had a supply of labour to help increase their wealth. Many went to the New World. Some stayed on as farm workers on pitifully low wages.

The poet John Clare reportedly went insane with grief at the loss of the common land from his local area. He describes the tragedy in many of his writings. The following excerpts are from The Mores a poem written by John Clare in 1820.

Describing the countryside before enclosure:

Still meeting plains that stretched them far away

In uncheckt shadows of green brown, and grey

Unbounded freedom ruled the wandering scene

Nor fence of ownership crept in between

And after enclosure:

Fence now meets fence in owners’ little bounds

Of field and meadow large as garden grounds

In little parcels little minds to please

With men and flocks imprisoned ill at ease

Telling of the devastating effect on the livelihood of common people:

Inclosure came and trampled on the grave

Of labour’s rights and left the poor a slave

The loss of a lifestyle in harmony with nature:

While the glad shepherd traced their tracks along

Free as the lark and happy as her song

And:

Mulberry-bushes where the boy would run

To fill his hands with fruit are grubbed and done

And the ending of the right even to access the landscape:

Each little tyrant with his little sign

Shows where man claims earth glows no more divine

But paths to freedom and to childhood dear

A board sticks up to notice ‘no road here.’

There was consistently vigorous opposition to the enclosures, with many rebellions and protests over the centuries. Invariably, on each piece of land where it occurred, the local people who had enjoyed customary rights to the land, the commoners, would interfere with the work of the surveyors, tear down the new fences and level the ditches and banks which enclosed the new fields. The military was often brought in to supress the resistance. It is notable that the landowners and government developed the strategy of frequently changing the detachment of troops to a particular place, as the soldiers quickly sympathised with the cause of the commoners. In parliament, in the media, and through pamphlets, the debate persisted through the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

With the Members of Parliament also being the landowners, people had barely any political or legal means to campaign against the enclosures. In losing their rights to the land, the common people lost their livelihood and their way of life. The arguments given in favour of enclosure drew on the concept of progress in the form of agricultural ‘improvement’, saving the common people from indolence, and giving them an opportunity to earn a wage. The real reason was quite simply the greed of the people in power.

As Simon Fairlie describes in his review A Short History of Enclosure in Britain the depopulation of the countryside was not mirrored in other European countries. And it had lasting effects globally. Some of the people who lost their land emigrated to the New World and contributed to the theft of land from the people there. Mainly, the enclosures turned rural smallholders into city slumdwellers. The surfeit of landless labourers kept wages low in the factories and the British cotton industry was able to undercut and destroy thousands of local industries around the world. Losing our access to the land did not improve the lives of the common people, nor did it make the world a better place. Within one generation, the connection to nature and the skills to live from the land became folk memories.

The story of the Mandobo of Papua is a recent and distressing account of people realising too late that they have been tricked into selling their forest, and with it their way of life, to a giant palm oil corporation.

Mark Boyle in his books The Moneyless Man and The Way Home portrays how it is possible to live without money in 21st Century urban England and rural Ireland and, significantly, the sense of satisfaction and contentment that comes with living in this way. Access to land for accommodation and for food is of course fundamental to living without money. Another helpful factor is a landscape that is accessible and abundant with wild produce, for example fish and fuel wood.

The consistent difference between those societies that work in harmony with their environment and those that destroy the basis for life is the use of money. Societies without money satisfy their needs for food, clothing, shelter and community without over-exploiting their environment. Moreover they are able to do this in fewer working hours than we work in industrialised societies, see for example Stone Age Economics, by Marshall Sahlins .

Introduce money into the economy, and you introduce the production of surplus and superfluous produce and the incitement to greed and consumerism, with the concomitant poverty, long working hours, separation and environmental destruction. Dr Gabor Maté observes, “Consumerist society depends on the creation of artificial needs.” See for example Russell Brand’s interview with Dr Maté .

It is a mistake to view subsistence cultures as being non-destructive as a result of being less socially sophisticated. The evidence points to the contrary. Deliberate rational choices are made by these societies. For example, Nemonte Nenquimo tells us that the knowledge of Indigenous peoples is to do with thousands and thousands of years of love for this forest, for this place. Love in the deepest sense, as reverence. This forest has taught us how to walk lightly, and because we have listened, learned and defended her, she has given us everything: water, clean air, nourishment, shelter, medicines, happiness, meaning. And you are taking all this away, not just from us, but from everyone on the planet, and from future generations.

For tribal people in North America their culture, economics, spirituality, ethics, education and governance provide a cohesive framework for living with respect for all species and as a positive presence in the environment. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer is a contemporary account of tribal society in North America showing how all these aspects work together to create a sustainable society.

Benjamin Franklin wrote an essay in 1784 titled Remarks Concerning the Savages of North America in which he expresses admiration for the Native Americans.

Of their civil society he wrote, … all their government is by counsel of the sages; there is no force, there are no prisons, no officers to compel obedience, or inflict punishment. Hence they generally study oratory, the best speaker having the most influence.

On their use of time, Having few artificial wants, they have abundance of leisure for improvement by conversation. Our laborious manner of life, compared with theirs, they esteem slavish and base; and the learning, on which we value ourselves, they regard as frivolous and useless.

Having frequent occasions to hold public councils, they have acquired great order and decency in conducting them. Franklin goes on to describe the procedure of the councils.

And their good manners: The politeness of these savages in conversation is indeed carried to excess, since it does not permit them to contradict or deny the truth of what is asserted in their presence …

A theme in Bruce Parry’s film Tawai, is the deliberate and rational choices that tribal people in different parts of the world make about how they live. They know how to live best in their environment through wisdom and a connection to what is valuable.

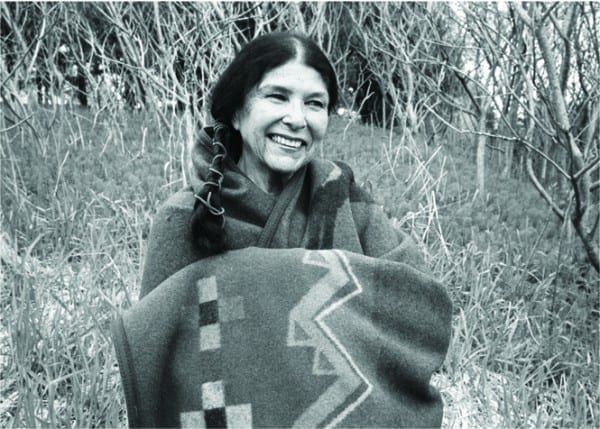

In conclusion, it is worth recalling what American film-maker Alanis Obomsawin said in 1972:

Canada, the most affluent of countries, operates on a depletion economy which leaves destruction in its wake. Your people are driven by a terrible sense of deficiency. When the last tree is cut, the last fish is caught, and the last river is polluted; when to breathe the air is sickening, you will realize, too late, that wealth is not in bank accounts and that you can’t eat money.

We are becoming aware that simply tweaking our economic system will not be enough to resolve the problems it is causing, that a much deeper level of reform is required. While the need for change is frequently recited, the discussion seems to be short on vision of what an economic system that provides for our needs without destroying the planet might look like. And yet the answer is in front of our eyes – in the livelihoods practiced by our ancestors and the few remaining tribal and subsistence cultures, many of whom are asking to be heard. Our immediate need is to stop depleting our natural wealth and to restore abundance to the world.

* Acknowledgement:

Many of the ideas presented here are informed by discussions with Salima Hirani, whose forthcoming book In Our Nature vividly presents how a localised, village-based economy comfortably provides for our needs.

Thanks so much for this, Simon – an inspiring read! I’m interested in the ways in which our publicly owned forests might help provide for more of our needs in future, and the personal and political reassessments that might involve. You’ve given me some really useful pointers here.

Brilliant article. Thank you for encouraging hope.